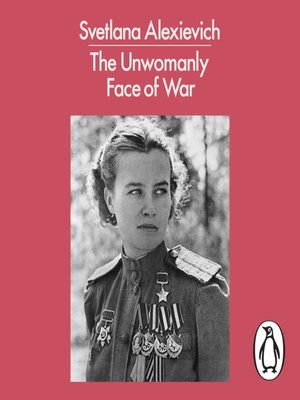

War, she realised, is seldom told from the woman’s point of view, and what interested her were not tales of heroism, but of “small great human beings”. Alexievich’s project began when she read an article in a Minsk paper about a farewell party given for a senior female accountant who, as a sniper during the war, had killed 75 people and received 11 decorations. Photograph: TASS/TASS via Getty ImagesĪ million women fought in the Red Army. Soviet pilots Vera Tikhomirova and Mariya Smirnova, 1942. A “writer, reporter, sociologist, psychologist and preacher”, she sees the world as a chorus of “individual voices and a collage of everyday details”. But today, when things happen so fast that the human mind cannot absorb them, “there is much that art cannot convey”. In the days of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, she has said, she would probably have written fiction. Alexievich left school to become a reporter on the local paper before devoting her life to collecting oral testimonies in order to document what it had been like to live through some of the defining traumas – the Chernobyl nuclear disaster and the fate of the Russian soldiers in Afghanistan – in recent Soviet history. The talk, in the village in Belarus where she grew up, was all of war most of its inhabitants were widows. Her father was the only one of three brothers to come home. Close relations had been killed, died of typhus or been burned alive by the Germans. The simpler the women, the more their stories were “uninfected by secondary knowledge”.Īlexievich herself was born in 1948 into a family scarred by the war.

For the rest, the women poured out their memories to her, not simply recounting them, but reimagining them. “How, in the midst of chaos? Begin by making me a woman,” she told him. When, in the ruins of Berlin, her future husband proposed to her, she had been outraged. One former pilot, who turned her down, told her that she could not bear to return in her mind to the three years during which she had felt herself not to be a woman. Very few of those she approached refused to talk to her. Over seven years in the late 1970s and early 80s, she interviewed many hundreds of women, the pilots, doctors, partisans, snipers and anti-aircraft gunners who served on the front line, and the legions of laundresses, cooks, telephone operators and engine drivers who backed them up. This sense of absolute directness and immediacy lies at the heart of Svetlana Alexievich’s extraordinary oral history of the Russian women who fought in the second world war, translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)